Life and work of Frederick Thomas Steerwood - Motoring Artist

Tekst alleen in het Engels

According to his own calculations, the motoring artist F.T. Steerwood made more than 10.000 studies, sketches, and paintings. His watercolors were published on the front covers of many magazines. Then why is it that we all have heard the names of contemporary motoring artists like F. Gordon Crosby, Harold Connolly or Bryan de Grineau, but Steerwood’s name is unknown? Why does his work not appear in today’s auctions? Time to find out more about:

Fred Steerwood, the forgotten motoring artist

By Rutger Booy

Fred Steerwood at age 40, always with a pipe

Hunt scene, circa 1927

The motoring magazines that were published during the early years of the previous century used artists to illustrate advertisements and articles about motor cars. These artists often proved exceptionally talented and today some of their illustrations have become real works of art. Their paintings fetch unaffordable prices at auctions. However, there were many artists who produced fine art. Some of their work survived, although most artists are now forgotten. One such artist is Frederick Thomas (Fred) Steerwood (1888-1965).

Fred Steerwood was an English artist who specialized in watercolors of motor cars. His artwork is remarkable for its soft bright colors, although he was also very competent in black-and-white studies and sketches, either with monotone gouache or pen and ink. He painted all kinds of cars, but a considerable proportion of his work was done for the motor manufacturers Austin and Morris. He produced mostly artwork that was used on the front covers of motoring magazines, such as The Motor Owner, The Autocar and Motor Transport. Several motorcycle magazines, for instance The Motor Cycle, and other magazines like Country Life and Homes and Gardens also published his watercolors. Apart from painting motor cars Fred Steerwood produced other works of art with different motoring subjects. After World War II his artwork changed, no more automobiles, but mainly landscapes.

Landscape with cows

The name Steerwood is a rare name that can be traced back to 1756. The Steerwood's were genuine Londoners, all living in the borough of Tower Hamlets directly eastwards from the Tower, outside the city wall. They were mostly artisans, for example dyers and cabinetmakers.

Fred's father Thomas Steerwood was the first to leave Tower Hamlets. He moved a few miles westwards to Clerkenwell EC1 (Borough of Islington) near the place where the family of his future wife Sarah Jane Willott lived.

Thomas and Sarah had nine children; they were all born at 26, Warner Street. The house is gone now; it was probably destroyed in the blitz during World War II. Frederick Thomas Steerwood was born in March 1888 as the third child after two girls.

Fred Steerwood (left) in 1893, five years old

Fred started drawing at the age of six, although in a 1960's letter to his cousin Yvonne, he confessed that he could not remember much from those days. He thought he had inherited his talent from his mother.

Due to the family being poor his schooling was inadequate. He went to an ordinary school but being a weakling (Fred's own words), he learnt nothing. He was handicapped because of bad stammering, making him almost dumb. Because of this, with its nervous reaction, he used to wonder what he would do when he grew up. Even running errands for his mother, he would do anything not to go, and he used to walk to and from outside the shop, sometimes crying until he would pluck up courage to blurt out what he had to buy. He found no need to talk much in his young days, and he was afflicted until he was well over fifty. During the Second World War, he worked among lots of young people, which helped him to forget his problems. Strangely enough this handicap didn't afflict him when singing, because in his youth he became a top choir boy.

He was sent to the Hornsey School of Art - a college in Crouch End, Hornsey, when he was seven years old; although this meant that his wider education was therefore lacking. In hindsight Fred Steerwood thought his parents did the right thing, as his presence in a classroom was terrifying for him, when he had to stand up and repeat things. It was only after he left school that he pulled himself together and went to evening classes. At that time, he could not even spell simple words, but in evening school he advanced famously, learning (again in his own words) "...most of the places in the world, decimals, algebra, electricity and all other things that good education gives." In 1905, at the age of seventeen, he even came eight in an open Civil Service exam of 2000 entries.

It is not known where Fred Steerwood started working after he left school. In a letter he wrote that for years he did eight hours of office work in London; went to art school at night and spent most of his waking hours with pencil and paper.

During the Great War of 1914-1918 he served in the Navy. One of his relatives still has a copy of a letter from Buckingham Palace to the boys' father. Dated 1915 it expressed... "His Majesty's appreciation of the patriotic spirit which has prompted your six sons to give their services at the present time... for their country and the British Empire". All of them survived the war.

This picture was taken somewhere in the period 1915-1920 (?). On it is written in pencil: "Royal Flying Corps" and "Fred Steerwood (on the right) with unknown colleague". Apart from the fact that Fred Steerwood served in the Navy during the Great War, the uniforms are not RFC uniforms, perhaps not even uniforms at all. This picture was taken during a demonstration where ex-WW I fighter pilots took people up in the air for a fee.

In September 1918 Fred Steerwood married Dorothy Shaw. They lived in Edmonton, North London. Not long after their marriage, Fred started his career with The Motor Owner, a high-class monthly magazine in the UK that was first published in 1919 and finished in 1931. The Motor Owner had a lot of full colour advertising, which was quite unique in those days as most British magazines were still printed in black-and-white. The publishers of The Motor Owner had their own art department where Fred Steerwood worked as a staff artist up to around 1923.

The early work of Fred Steerwood can be difficult to spot, because painting the cover for a magazine is a specialist kind of art form. The artist not only has to create the painting, but he also must make room for the logo of the magazine in a way that does not interfere but blends in with his painting. Sometimes the artist was not allowed to sign his artwork. This means that early watercolors of Fred Steerwood, and later his smaller works, are not always signed, although many can be attributed to him because of his recognizable style. Also, text or small advertisements could have been placed over part of the art, thus masking the signature.

His first artwork appears in the July 1919 issue, which he signed with a monogram: an "S" in a part circle, or a single "S" in which the "S" is quite similar as in his full signature of those days. There are several of his works with this monogram in 1919 and 1920. Then from July 1919 followed several artworks that he signed with F.T.S. From 1920 on all his work bears his full signature.

![]()

Steerwood monogram oval

Steerwood signature FTS

Steerwood signature s

Steerwood signature

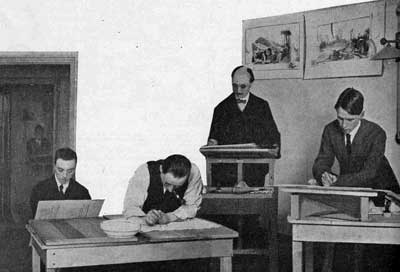

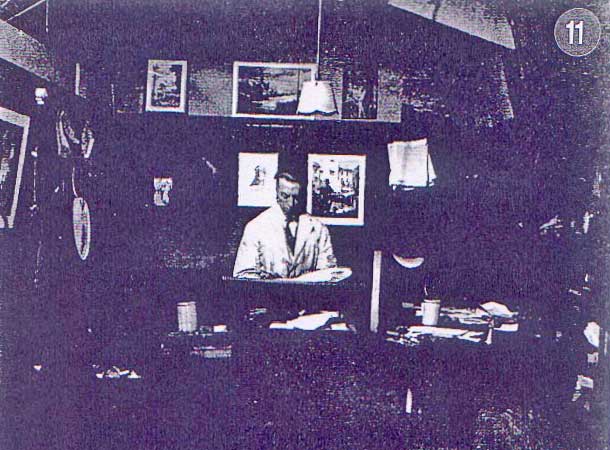

The artists of "The Motor Owner", with (probably) Steerwood in the foreground. Although he has his head down, he is smoking a similar pipe as on the photo above. Fred Steerwood was the principal artist at the magazine so it is logical that he should be at the front of the picture (photo published in "The Motor Owner", November 1919).

Fred Steerwood (on the left, with pipe) at age 31, working on the advert for "Clincher Motor Tyres" that was published in the December 1919 issue of "The Motor Owner". Click here for full advert (photo published in "The Motor Owner", November 1919).

By then Steerwood had become a very prolific motoring artist. For example, the December 1919 issue of The Motor Owner published fifteen of his paintings. The Motor Owner paid Fred Steerwood a salary but when in the early 1920s the magazine reduced the original art they used, he became a freelance artist and was paid for each illustration. This allowed him to look for work elsewhere.

At that time, the motor publishing world was dominated by two rival titles, The Motor and The Autocar, published by respectively Temple Press and Iliffe and Son. Both magazines only had a color front cover and an occasional special feature, also in color. Being a freelance artist made it possible for Fred Steerwood to work in part for The Autocar and he produced many front covers and several other works of art for them.

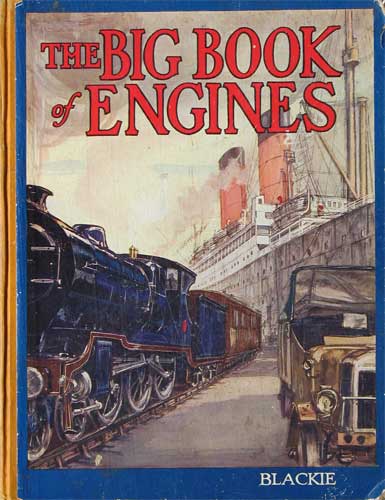

Another of his commissions came from publisher Blackie & Son in London. One of their projects was a children's book, titled The Big Book of Engines. The book is not dated, but I suspect it was printed in the 1920s. It's a collection of 36 colored plates of trains, ships, and vehicles. Fred Steerwood's contribution to this book was a series of twelve paintings depicting several forms of motoring transport. The colored plates in this book are simpler, even less inspired than his other work. There is no real detailing on the paintings, not even brand-names on the motor cars. It doesn't seem important; the plates show only the stereotype of several forms of transport: buses; fire-engines; the mail van; the saloon and the tourer. Is this because it's a children's book? Furthermore, it's strange that nowhere in the book the names of the artists can be found. Only their signatures on the plates are a giveaway of their identity. And as an aside: there's little difference in the manner of painting the trains, ships, and automobiles. It could very well be that all plates have been painted by Steerwood.

Another children's book he contributed to, was The Big Book of Motors but it is suspected that he provided illustrations for several books.

In 1922 Fred Steerwood and his wife Dorothy moved to Muswell Hill in London. A few years later in 1927 they moved again, this time to Welwyn Garden City, north of London. Their new house, situated at Oaklands on the edge of Welwyn Garden City, had a separate atelier where Fred spent most of his working artistic life.

The house and atelier in 1934

The house stood at the top of a steep slope with fir tree woods, but it has been torn down. The house was called 'Moy Domik', but it is not known why. It could be Russian; in which language it means "My house". But why Russian? What's the connection?

Apart from his painting skills, Fred Steerwood also had a technical talent. He had, for instance, made his own radio, a crystal set. As a person he must have seemed reserved, maybe because of his stutter. On the other hand, he was also friendly and had humor. He always smoked a pipe and enjoyed company over a glass of beer in local pubs.

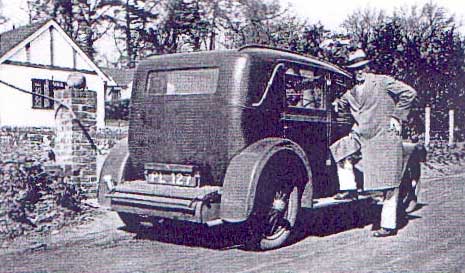

Fred with his motor car, a Talbot manufactured by Clement Talbot Ltd, Barlby Road, London. W10. The model is a 14/45 with a Weymann Saloon Deluxe body by Darracq Motor Engineering Co. Ltd. The PL registration mark indicates that the car was registered in 1930 in Guildford.

Photos above: with brother Bert and sister-in-law Nora, ca. 1934; (click here to see the dog!)

Fred Steerwood at age 59, looking very relaxed

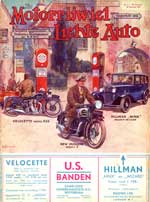

Apart from his work for The Autocar, Fred Steerwood painted covers for Dutch magazines De Auto and Het Motorrijwiel en de Lichte Auto. De Auto was published by the KNAC, the Dutch version of the RAC, and a sister publication of The Autocar. These front covers and special artwork were not mere copies of his work for the British magazines. Most were specially made as they show characteristic Dutch landscapes with recognizable, medieval towns and typical Dutch windmills. In the 1928 Jubilee issue of "De Auto", issued to celebrate the twenty-fifth year of this magazine, a picture of Fred Steerwood is published, along with the rest of the staff and he is described as "F.T. Steerwood, our English Artist".

During the early years of the 1930s there was a notable fall in the output of Fred Steerwood's work. One explanation could be that The Autocar started using photo sourced artwork for their cover designs. However, unlike the imagination of an artist, a photo camera clicks at the moment the action happens. With his pencil or paintbrush, the artist can go backward or even forward in time and is thus able to depict events as they had happened and were not captured on camera. This meant that illustrators were still needed by magazines to add some excitement to the stories.

In 1933 Fred Steerwood moved on to The Morris Owner. This magazine was started in 1924 by Miles Thomas (later Sir Miles of BOAC-fame), who had been given the task by William Morris (later Lord Nuffield) to "...consolidate the family feeling among owners of Morris cars and to give them advice on how to get best results from their purchases." In his autobiography 'Out on a Wing' Miles Thomas wrote (page 129): "...The Morris Owner was an initial success because I managed to bludgeon the various suppliers, Lucas, Dunlop, Rubery Owen and others, into buying advertising space, and equally I sold it through the chain of agents that had been created for the distribution of the Morris Car. And surprisingly enough the magazine became established with the public on the bookstalls, due perhaps to my utilisation of various artists and writers that I had contacted during my Temple Press days."

As Fred Steerwood contributed to The Light Car & Cycle Car, a magazine published by Temple Press, he was among the artists recruited by Miles Thomas, only at a much later date. His first known cover for The Morris Owner dates from September 1933. Steerwood produced much artwork for them, his peak year being 1937 when he was responsible for at least six front covers.

During the late 1930s and early forties the subject of Steerwood's artwork changed due to the outbreak of World War II. In September 1939, The Morris Owner still had a picnic-scene on the cover, but February 1940 showed a clear change: a Portsmouth Harbour Scene with sailors and a Morris with Hartley headlamp mask due to the blackout. The September 1942 issue had a Blenheim Bomber prominently on the cover and the cars were hardly visible on the coastal scene.

Nothing is known about the war years of Fred Steerwood; although it seems safe to assume that both his talent for drawing and his interest in radios were used, just like Bryan de Grineau becoming a war artist producing for the war effort. It is certain that after the war Steerwood worked for the Marconi Corporation in Essex, where he produced technical illustrations.

After World War II the artwork of Fred Steerwood changed from motor cars to landscapes. As he was by then already in his sixties, he retired, allowing him more time to produce other artwork. In a letter dated May 10, 1950, he wrote: "I am studying oil painting or experimenting more seriously than I had time to do whilst doing commercial watercolor work... small imaginary studies of landscape... quite surprising... of course, I did a few studies years ago." And in a later letter he wrote: "... I have always had the confidence that I can stand my own ground with the many millions of ordinary folk. This is not conceit, but it is to my credit as I gave up a great deal of my youth to attain this end."

Several years after his wife Dorothy died in the early 1950s, Fred married Irene Browning, widow of his younger brother Walter. This marriage did Fred a lot of good, as he had felt very lonely after Dorothy had died. In a letter to his cousin, he wrote: "...lack of affection of years duration had a pronounced effect on me, although I did not realize it at the time. Living alone isn't too good for one, if, by chance, one is born a friendly sort of person." But in the same letter he also complained that Irene preferred mostly plain walls, so: "...our house shows very little of one of its inhabitants having an artistic nature."

The last years of his life Fred Steerwood lived in Southsea near Portsmouth, where he rented an apartment above a shop. Why there is not certain, a connection could be that his younger brother Bertram lived in Worthing on the South Coast, not far away. One Sunday morning he woke up scarcely able to breath. Two doctors diagnosed a thrombosis of the heart. He recovered but had to take it slowly from then on. He died on June 23,1965 in Southsea at the age of 77. Three days later he was buried in Milton Cemetery. In 2006 his grave was still there although not noteworthy amongst the hundreds of other tombstones.

The inscription on his tombstone reads: "In loving memory of Frederick Thomas Steerwood, Died June 23rd, 1965, Aged 77 years, Rest in Peace" (photo taken in September 2006).

Fred Steerwood had no children, which he regretted. He thought it was a pity that he did not have at least one son that might have shared his love for art. According to Fred's own calculations he had made more than 10.000 studies, sketches, and paintings during his lifetime. After his death some of his artwork was distributed amongst the family, although nowadays very few originals are known to exist. Where has it all gone? Presumably most have been destroyed, some of them during World War II as factories were bombed. Also, many of his originals would have ended up in archives of the various magazines and later scrapped to make room for other paperwork. One picture was found inside a fire screen covered by a tapestry. This was an incredibly lucky find of course, as even at the local museum in Southsea, where Steerwood had lived for several years, they had never heard of him.

Then there is still the question why artists like Gordon Crosby and Connolly are well-known and Steerwood's name has been forgotten. Could it be because he did not paint the racing and action scenes that are so much loved by racing enthusiasts? True, as Steerwood only painted motorcars in a landscape. These were 'pretty pictures' that give you a sense of 'feel good' or 'I want this too', a feeling which is exactly what his paintings are meant to portray. Steerwood's pre-war work was solely commercial, in a lot of ways like Gordon Crosby, the difference is that The Autocar publicized Crosby's work with free picture supplements and exhibitions of his work, and as a result his art was saved at the time. Harold Connolly is remembered for his wonderful artwork which was used to illustrate all the MG catalogues and leaflets from 1929-1939. Other motoring artists have not been so lucky, and Steerwood's art survival rate is typical of pre-war commercial motoring art. Still, the art of Fred Steerwood comes in a class of its own and he deserves to be remembered. Will we ever find more of his work?

With thanks to John Steerwood sr. and Tony Clark for sharing his knowledge and advice.

Steerwood family tree